Svalbard, The Arctic, May 23-June 1, 2015

It’s not exactly a hop, skip, and a jump from saltwater crocodiles to polar bears, but I left tropical Australia on a Tuesday and by the end of the week I am walking up the main road of Svalbard’s only town, Longyearbyen, toward the glacier at the end of the valley. Svalbard is an archipelago located 500 miles north of Norway and 500 miles south of the North Pole. Svalbard is a protectorate of Norway, Spitsbergen its largest island, and Longyearbyen, which dates back to 1896, the administrative center of the islands.

The town’s population of 2000 is outnumbered by the more than 3000 polar bears wandering the archipelago, and you’re not allowed to wander outside city limits without either carrying a rifle for protection, or being accompanied by an armed lookout. As I wheel my duffel into our hotel, I note that cornices overhang the ridges on both sides of the narrow valley. Last year an avalanche munched its way through town and took out a bridge. The temperature is predicted to range from 30 to 33 degrees each day, and there’s 24 hours of daylight, which is perfect for melting the snows above. In short, my kind of town. Did I mention that Longyearbyen hosts one of the largest wine cellars in Northern Europe?

Svalbard was at first a whaling station in the 1600s, then at the beginning of the 20th century a coal producing center. The coal is mostly played out now, although the Russians still mine some in Barentsburg just down the coast—their way of maintaining a strategic presence on the island—and there’s one other mine nearby that fuels Longyearbyen’s power plant. But now the economy of the archipelago depends increasingly on Svalbard’s growing tourism and scientific research. It’s notable that the researchers are studying everything from polar bears to the aurora borealis, exactly what the tourists come to see. Extreme landscapes present not only our desire for sublime views, but also the edge of knowledge.

I’m here with the Future North project from the Oslo School of Architecture and Design—the same group that brings me to Norway every January to study changes in the circumpolar Arctic as the ice goes out and people move in. It’s more than a little ironic that the Global Seed Vault stands is on the edge of town near an abandoned coal mine. The burning of fossil fuels has ignited global warming, which shows up twice as fast in the Arctic as elsewhere, and is making Spitsbergen each year a less suitable place for a freezer devoted to preserving biodiversity.

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Note the illuminated artwork by Dyveke Sanne. Architect: Peter W. Söderman at Barlindhaug Consult AS. Image courtesy of the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food.

The Future North team spends the week of our visit walking transects through the town and interviewing locals, looking for manifestations of how the transition from resource extraction to knowledge creation is proceeding. My job is to research how art has been deployed since the 1800s to create the brandscape of Svalbard, which is related to what I was doing in Switzerland in September of last year, and also in the Australian Arnhembrand project the previous week.

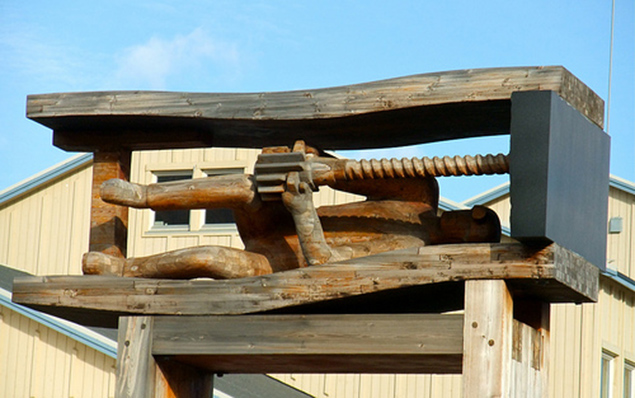

One evolution I document is the progression from statues of miners commemorating industry, to a metal polar bear, to a tower constructed from floating plastic harvested in the harbor. What interesting is that the timeline of the progression is so compressed. Homages to founding figures and totemic workers in other European locations were often erected in earlier centuries, then followed by abstract sculptures, and eventually place-making amenities. The wooden sculpture The Miner created by Norwegian Kristian Kvaklands—a horizontal figure drilling a coal seam between claustrophobic layers of wood—was created in 1993. A less effective, if more traditionally heroic bronze sculpture of the same title by Tore Bjorn Skjølsvik stands just down the street, and was created in 1999.

Representations of polar bears are ubiquitous throughout Longyearbyen, starting upon your arrival at baggage claim where a taxidermic one scowls at your luggage from atop the carousel. A few blocks from the miner stands one of the more recent versions, a life-sized beast executed in stainless steel outside the office of filmmaker Jason Robert, who commissioned the work in 2011. Its overlapping sheaves of metal are vaguely heraldic, and evoke myth as much as reality.

Peter Hemmersam spots a colorful two-story tower made of plastic waste harvested from the local shoreline, and when we investigate we find a door into the tiny first-floor where a couple of college students are sharing a beer. The floor of the second story is clear and you can peer upwards to continue your visual inventory of the plastic items. The sculpted found-object architecture was created by Solveig Egelund in 2014, who has done similar projects at other sites.

Peter, in the meantime, has been investigating two buildings in town that display the shift from mining to research. The angular and multi-limbed Ropeway Hub, where several tram lines converged bearing hoppers of coal, sits above the power plant. It was built in 1957 and is a striking piece of vernacular architecture. The Svalbard Science Center, a multi-faceted facility, was erected in 2006 and servers as an international hub for researchers, Both are metal-clad and perched on stilts. While the Science Center was designed to echo the shapes of the mountains across the fjord, it also resonates with the functionalism of the Ropeway building, which residents hope to turn into a cultural center for tourists.

The Ropeway Hub above the power plant in Longyearbyen. Photo courtesy of the Swedish Polar Research Secretariat.

The conjunction of science and tourism in this northernmost town of more than 1,000 people is a unique circumstance. Three years ago there was almost no winter tourism in the archipelago; now the town is packed on New Year’s with people flying here in hopes of seeing the Northern Lights, even as the scientists are monitoring the auroral activity. The artwork by Dyveke Sanne along the roof of the Global Seed Vault and down its front is a fine metaphor for the combination. Consisting of highly reflective triangles of stainless steel that reflect the Arctic light during the day, during the long night it is lit by fibre-optic cables refracting through prisms, which evokes the aurora. The artwork is both a reflector and a beacon—in literature a duality referred to as “the lamp and the mirror.” At times it reflects the world, but at others actively illuminates it, a good enough metaphor for tourism and science.

Dyveke Sanne, Perpetual Repercussion, 2008. Photo by Mari Tefre/Svalbard Globale frøhvelv. Image courtesy of the Norwegian Ministry of Agriculture and Food.

This post was also published at the Center for Art + Environment Blog.

Feature Image: Spitsbergen during approach for landing. Photo by Hannes Grobe courtesy of Wikipedia.