Walking the High Wire

In January 2014 the Future North team and guest researcher Bill Fox (from the Center for Art + Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art) visited Vardø on the Barents Coast.

The wind where the street ends and the sea begins is gusting over five meters per second, enough to stagger us while we’re standing above the massive green combers pushed out of the Barents Sea. Spindrift blows sideways through the rocks. It’s -5Cº, and we’re wearing multiple layers of fleece, wool, and windproof nylon against the wind chill. Taking notes is done with bare hands facing away from the wind in 15-second bursts.

The uppermost street atop Vardø sweeps in an arc with its apex the easternmost manmade civilian feature on the island. The handful of houses planted along it, which are afforded spectacular views of the waves and rocks, are generic family dwellings that could be sitting in any northern European city, a banal suburb fronting the sublime. The only structures sitting higher and more easterly than the tidy dwellings are four radar domes. It’s not coincidental that on a clear day you can see the mountains of Russia from here.

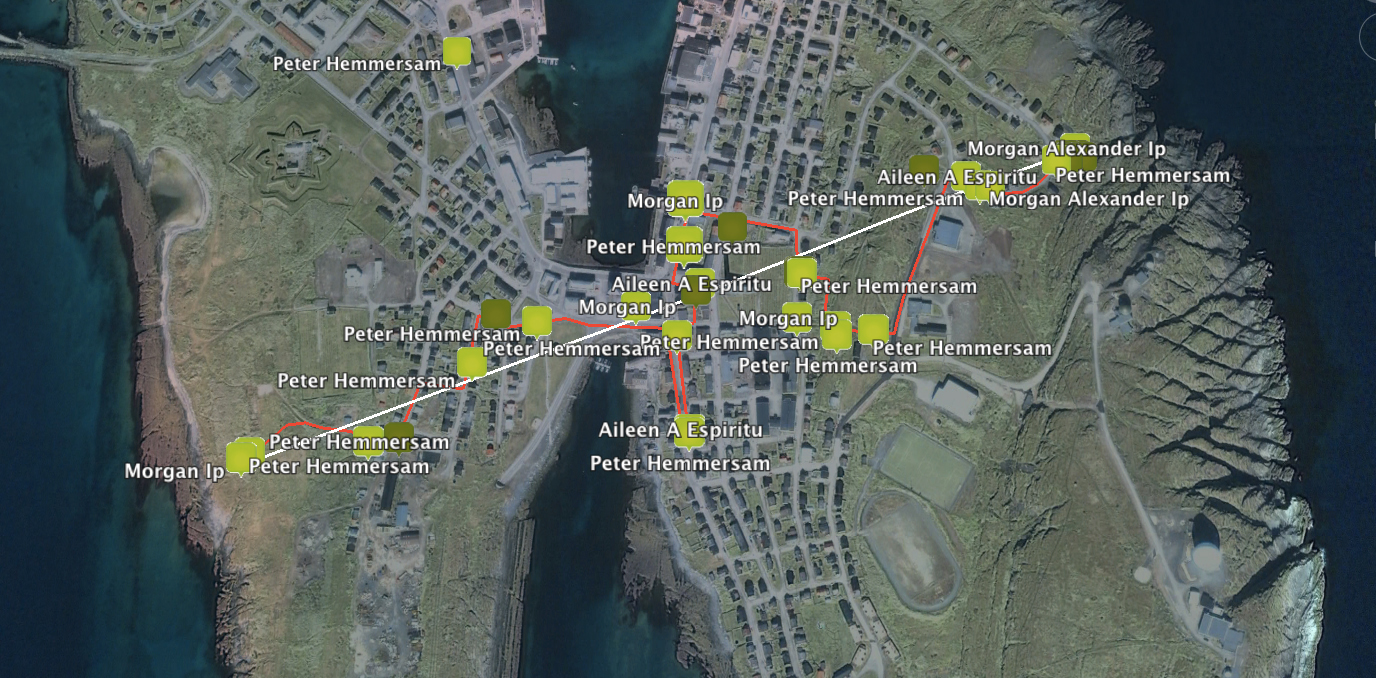

The transect of Vardø that Peter Hemmersam has plotted for us starts here above the eastern shore, cuts through downtown and across the historical harbor. It then traverses the left lobe of the butterfly-shaped island to end on the western shore not far from the spindly radio masts of the Vessel Traffic Service. In between stands the improbably tall isosceles spire of the town’s central church. What the transect walks is a line stretching above town that connects its three highest points, all of which are navigational devices for military, commercial, and more ethereal movements.

The four domes atop the geological climax of the island serve several masters: the Norwegian Intelligence Service, which administers them, the Raytheon Corporation which built and maintains the largest one, and the United States Air Force Space Command, which ostensibly deploys that latter device, the 27-meter radar dish of Globus II, to track space debris. And you can see Russia from the doorstep of its three-story building supporting the huge white dome, which is by far the dominant visual vertical on the island. A good guess is that the multiple devices track everything that’s flying above the ground flying north from Iran to Murmansk, as well as the 10,000 pieces of trash in slowly decaying geosynchronous orbits.

As we trundle down the snow-covered street the twin crosses capping the church spire are visible most of the way. The first church in the center of Vardø was built in 1307. A more recent version constructed in 1869 was torched by the Germans in 1944 as they retreated from northern Norway. The current Church of Norway structure, its interior a slightly chilly and austere mid-century Lutheran chapel, doesn’t see much traffic on Sundays, but remains an important civic center for rites and passages, as well as the occasional concert.

But the dominant height of the spire, while it metaphorically connects Heaven and Earth, is a reminder that church spires were often the most or only visible landmarks along an otherwise foggy, highly fractal, and isotropic coastline. Ship’s logs contained a catalogue of them all along the shorelines of this part of Europe, distinctive features standing above each town that the pilots used to keep place in the grayed-out world of water and sky that is the Barents Sea.

The several radio masts and real-time tracking screen of the Vessel Traffic Services is part of a cooperative monitoring system run in cooperation with Russia. The “VTS” tracks every boat and ship on the sea surface around the region, paying particularly attention to the shipping routes from Lofoten archipelago north around the Varanger and Kola peninsulas to Murmansk. Liquid natural gas and oil tankers, ships carrying nuclear waste, and the commercial and passenger traffic through the increasingly ice-free Northeast Passage keep the operators alert. The system uses satellites, coastal radios, some of the radar gear atop the island, and maritime seniors to plot the constantly evolving relative positions of every vessel. Everyone prays it works, no doubt.

All three verticals are linked visually from almost any vantage point on the island, and they exist to plot, surveil, assist and sanction human movement in a profoundly hostile environment. The geopolitical and historical circumstances that require facilities of global strategic importance be situated in Vardø, an otherwise modest if handsome fishing town, illuminate why this has been a fortified stronghold in the Arctic since the late thirteenth century. As always, the most highly prioritized functions of a town are expressed in its verticals, which require the expenditure of more resources to erect than the horizontal and more earth-bound buildings of commerce and domicile. Peter’s transect followed a natural fall line from the most global of the instruments to the more regional coastal service.

Sources:

“A Globus II/Have Stare Sourcebook: Version of 2013-09-20” accessed on January 27, 2014 at: http://www.fas.org/spp/military/program/track/globusII.pdf

“Eyes on the Barents maritime safety” accessed on January 27, 2014 at: http://barentsobserver.com/en/security/eyes-barents-maritime-safety