Seven themes for the Second Oslo

Dominant models of sustainable urban design, such as compact city strategies, do not make much sense in the areas outside the central area of the Oslo region. This article lists seven themes that are important when the future city of the Second Oslo is to be conceptualized and designed.

A consensus as to how cities can meet the challenges posed by sustainability is emerging. The primary response of cities in terms of urban policy and planning can be summed up in the term ‘Compact City’. This is a strategy that is easy to envision for planners, politicians and the general public. It encompasses the idea that cities should be concentrated on smaller land areas to minimize the energy consumption that goes into transport and heating. Densification also supports walking, cycling and public transport, which are all environmentally friendly forms of transport.

It is often presumed that denser cities generate a friendlier and attractively mixed urban scene and lively streets. The policy of compact cities aligns itself with current ideas of what makes a city attractive and competitive in attracting new resourceful and discerning ‘creative’ inhabitants, corporations and tourists. The ‘recipe’ for being attractive is summed up in surveys like the annual Monocle index of the Worlds ‘Most Livable Cities’, which looks at living costs, safety, greenness, traffic, environmental policies, art, etc. In this and other comparable indexes the Scandinavian capital cities tend to be ranked in the higher echelon, due to factors like social welfare, general level of education, safety, greenness and environmental policies. In Copenhagen cycling is heralded as a major factor of quality of life that is linked to environmental awareness, and Oslo is ranked high due to access to carbon-free renewable energy and the green character of the city.

The compact city strategy for central cities may be easy for a city like Oslo to subscribe to, even though public protests tend to follow proposals for densification. Oslo has a relatively low density compared to other large European cities, so the potential for densification is definitely there in terms of space. Oslo is also currently growing at a faster pace than any other city in Europe, and the associated pressure on the housing market results in new and denser forms of urban environments than we have seen before, and a reduction in the size of newly constructed apartments. Finally, Oslo is historically developed around the armature of the subway (T-bane), which supplies it with an existing, efficient collective transport system with a capacity to support a greater number of inhabitants and businesses around the existing (and proposed) stations.

The Second Oslo

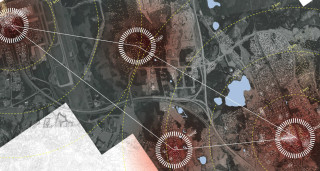

The strategies for compact city, however, do not make much sense in the areas outside the central area of the region. Outside the municipal boundaries of Oslo, a ‘Second Oslo’ has to be recognized as an existing situation with a population rivaling or even exceeding that of the central urban district. This ‘Second Oslo’ is a result of a disperse population pattern that started with the development of the railway in the late 19th century and early 20th century, and has accelerated with the general increase in car ownership in the last 40 years, and the associated development of infrastructure. And while these areas that encompass some of the fastest growing municipalities of Norway are often seen as secondary or auxiliary to the central city, they are increasingly the location of large metropolitan or even national programs like the Gardermoen Airport or the Expo at Lillestrøm, and can therefore no longer be seen as secondary to Oslo.

The Second Oslo as we see it today is fast growing and transforming at the same time. The underlying structure of small towns associated with railway stations still form the back bone of most of the communities, but the vast majority of inhabitants live in urban situations that bear little resemblance to the central city, and where ‘compact city’ strategies are not easily applied.

Emerging issues

The seven municipalities of the By- og tettstedsprosjektet in Akershus make up the substantial part of the existing and projected development in Akershus County, which surrounds Oslo on all sides. They are undergoing change and transformation in several parallel ways, and developing strategies for sustainable development in these situations is conceptually challenging, but also critically important as major restructuring of existing towns, residential and industrial areas as well as the infrastructure is happening at a fast pace – a development that is projected to continue in the decades to come. In many places we find that communities that considered themselves rural (‘bygd’), are now having to coming to terms with being city (‘by’).

Studying this fastest developing zone of the Akershus Region, a number of critical issues of policy, planning and the design of cities emerge:

1. Preparedness for change

When cities change new things are constructed, but other things are eliminated. In the last category we find noisy and environmentally problematic industry which was originally located ‘outside the city’ but is now found to be right in the middle of the Second Oslo, often in close proximity to new housing development or associated recreational areas. While they may be seen as unattractive, they often provide employment in municipalities that are otherwise dominated by residential functions, and it is hard for politicians and local administration to publicly consider the possibility of shutting them down or relocating them (to other municipalities). The process is on-going, and the conflicts will in many cases only increase. This calls for a kind of preparedness to embrace new economic conditions, which is otherwise associated with the small one-factory towns in the hydropower regions of the country.

2. No-growth planning

While the region is projected to grow in the next decades, this growth may take unforeseen forms, and distribute itself unevenly across the landscape of the Second Oslo. It is also entirely possible that the current projections will turn out to be entirely wrong, and that the expected growth may simply never appear as expected. In planning for the future, this contingency has to be considered, and what would appear as ideal locations for investment and development, may remain as waiting landscapes for the future. So, when planning for growth, the no-growth possibility should be considered, and the temporary character of ‘waiting’ land should be turned into something useful.

3. Quality and robustness

In planning and developing new spaces, landscapes and buildings, quality ensures sustainability in the sense that emotional investment of individuals in the physical environment ensures involvement. It provides the basis for a willingness of individuals to adjust and change lifestyle and of corporations and public bodies to deviate from strict capital investment logics in favour of preserving and transforming existing environments, rather than expending scarce resources on entirely new ventures. Only the beautiful is truly robust, and investing in quality may even turn out to be a great business idea.

4. Living with infrastructure

Infrastructure is the underlying logic of the Second Oslo. As development accelerates, so does the pressure to build new and better infrastructure, which results in negative environmental impact on surrounding districts. Measures for alleviating environmental degradation of neighbourhoods is high on the agenda, and involve the construction of sound barriers and reducing ground level traffic by constructive hugely expensive tunnels. While these measures are beneficial, a much more comprehensive set of strategies for the close spatial integration of urban districts and infrastructure is a highly coveted. Designers should invest time to develop entirely new modes of co-existence.

5. Avoiding sustainability parametrics

Just as heritage listing of urban areas restrict new development, environmental factors ‘occupy’ large territories in the Second Oslo. This may be in the form of buffer zones along roads, unbuildable strips under power lines, areas suspected of ground pollution, old waste dumps, protection zones around water bodies, etc. While all these measures individually make sense, added up they restrict development on large tracts of land, leaving unprofitable or inconvenient sites. This means that new development may be forced into forms and morphologies that counteract attempts at efficient, urban structures and circulation systems. In many cases confronting the environmental issues is essential to any new robust or sustainable development.

6. The problem of sectorial design

The physical surroundings of the Second Oslo are produced by a multitude of actors and agencies. Private individuals build their houses, developers and corporations build housing enclaves, industrial and commercial structures, and public bodies of various kinds build public institutions and shared amenities like public urban spaces and recreational areas. Other agencies, often operating at different levels of government construct roads, flight patterns overhead, nature reserves, or heritage preservation zones. All these bodies, belonging to different sectors all operate from different rationales, which sometimes do not align. What may constitute a safe traffic environment from the point of view of the road department may run completely counter to what local authorities or other government agencies of the working with social, cultural or environmental issues, consider appropriate or desired in a specific location.

7. Spatial policies outside planning

The conflict between preserving valuable agricultural land in the face of urban expansion is an example of the type of spatial issues that are addressed within planning. However, some spatial policies fall outside the remits of planning, for instance mining and resource extraction, which is regulated by a laws that far predates contemporary planning, and falls under entire other government agencies, with no or little interaction with planning. This division has historic roots, but in the urbanization that is taking place in the Second Oslo, many forms for land use administrations are uncovered and have to be addressed.

The Future City

The Second Oslo is the Future City, and its growth and development should reflect the fact that it has a history – both as a local place but also as a logic of offering attractive living and working environments with great appeal. Studies of the Second City should be critical to landscape architects, architects and planners.

This article is based on a study of the planning challenges in the Akershus Region was conducted with the Urban Design: Future City course at AHO in the fall 2011, in parallel with a study of the Second Copenhagen by Department 10 at the School of Architecture at The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation in Copenhagen.

Image by Randi Engan