The Contorted Architecture of Geopolitics

Together, two iconic buildings in Longyearbyen represent the changing logic of Norway’s geopolitical interests in the Arctic.

On Svalbard, all buildings are raised on stilts. The permafrost requires them to be elevated at least one meter off the ground, so the heat they emit does not melt the ground and make it unstable.

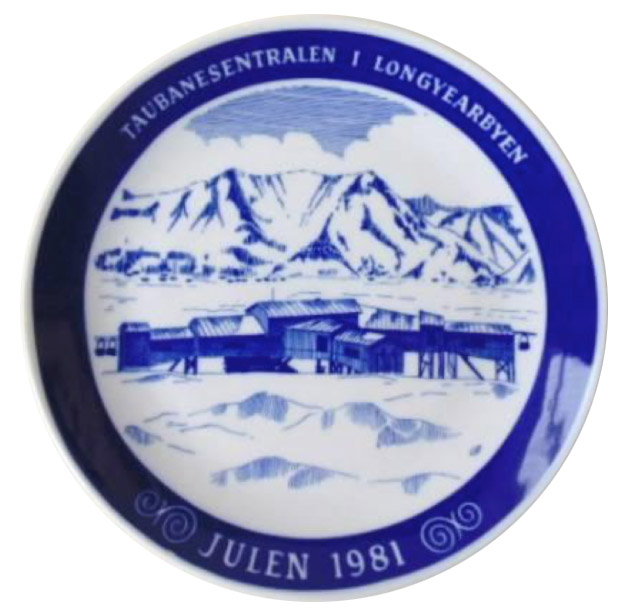

Built in 1957, the Ropeway Hub (Taubanesentralen) is an icon of the coal mining history of Longyearbyen. Within this structure, ropeway conveyers from several mines met, and the coal was sent off to the pier for further shipping. It is a strictly utilitarian structure – a piece of engineering – made from steel and corrugated plate and elevated on long legs to the level of the ropeway. It has a strange geometry, with several arms that project out towards the different mines. This irregularity is remarkable in a mining town where the buildings are strictly utilitarian, and often modular.

At a lower point in the city, closer to the sea, we find the Svalbard Science Center from 2006, designed by Oslo architects Jarmund og Vigsnæs. Outside the entrance to this building a slate tablet shows a 3D rendering of the building in a way that makes it look like a prehistoric animal who’s physiognomy has been contorted in the process of fossilization. This is an appropriate visual style that reflects the range of biological and geological sciences enacted at the center and in field in Svalbard, and it also refers to the fossilized energy (coal) that is the raison d’etre of Longyearbyen.

Both structures reflect the particular arctic conditions of Longyearbyen. The Ropeway Hub is pragmatically covered to shelter the equipment and workers inside from the elements, and the expressive form of the Research Center is the result of the architects’ preoccupation with the form-generating potential of the extreme climate: “Lifted off the ground and streamlined according to snow piling and wind efficiency, the architecture responds to the physical challenges of the arctic.” (1) The twisted volumetric body analogy of the architecture means that the building has to rest on stilts.

While the aerial ropeway hub is a steel construction and the research center is constructed out of wood, both buildings are clad in metal and raised above the ground – although for different reasons. Together, they reflect the change in the local community over almost 40 years: The ropeway building was a hub for coal that dominated the logic of the town for over a century, while the center is a global hub for researchers and tourists alike (in the building tourism and research meet in the Svalbard Museum).

Coal mining was historically the economically most rational way to claim Norwegian sovereignty over what was previously a Terra Nullius. However, increased focus on environmental damage as an externality of this activity and increased perceived importance of wildlife and untouched wilderness means that tourism and research may now actually be “more cost efficient than coal mining in order to maintain a presence and secure sovereignty”. (2)

The aerial ropeway hub is an icon of historical landscape exploitation – its limbs being extensions of the lines in the landscape that radiate out to the points where the underground coal seems were most accessible – the pitheads. The twisted body of the Research Center is an echo of the contorted shape of the ropeway hub: Its geomorphic form also conforms to, and generates, lines in the landscape: the pedestrian axis from the city centre, and the view line to the sea and the Advent Valley from the reading corner in the museum part of the building.

The Ropeway Hub is still the de facto architectural icon for the town (just have a look in the souvenir shops), while the expressive form of the Research Center, located at a low point in town, is really only easily perceived while passing round to its back, facing the road that divides the town from the harbor. The shifting geopolitical regime of Longyearbyen has still not resulted in new dominant architectural expressions.

(1) http://www.jva.no/projects/large/svalbard-science-center.aspx

(2) Sand, J.Y., S. Østbye, and O. Westerlund (2009), “Omstilling og omstendigheter – et samfunnsøkonomisk tilbakeblikk på kulldriften,” in Det Store Kullrushet – Industriell omstilling i Arktis, Mikalsen, K.H. and M. Solberg (eds), p 92.