Constructions of North

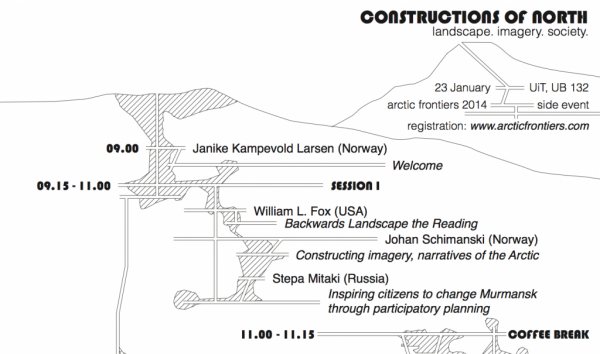

Last week, at the Arctic Frontiers conference in Tromsø, the sidebar conference Constructions of North was held. This all-day event explored both physical and imaginary outcomes from nine researchers working on, in, or near the Arctic region. The rich talks covered political, economic, and aesthetic means of understanding our conception of the north.

The day started with an introduction and welcome by Janike Kampevold Larsen and ended with a thoughtful response and moderation by Andrew Morrison. In between, the audience was treated to a focused analysis of several areas in the Arctic, texts about the urban landscape of the north, and definitions of what art and design can look like in this region. The conference started with a talk by Director of the Center for Art + Environment at the Nevada Museum of Art in Reno, William Fox, who asked us to “read backwards,” in the style of editor, when we look at northern landscapes, texts, and artworks. Reading backwards, he argued, would allow us to make strange everyday details about the environments in which we live, thereby allowing us to focus on their uniqueness as well as to discover what might be missing in them. His purpose was to encourage us to consider how we might give back to the locales in which we work. Fox’s discussion provided a great starting point for the conversations that were to arise out of the other speakers’ talks.

Johan Schimanski and Kathleen John-Alder continued the thread of reading backwards through their separate analyses of historical and contemporary texts about urban and rural landscapes. Schimanski’s work, with Ulrike Spring, focuses on Austro-Hungarian portrayals about Svalbard and Franz Josef Land in the popular media, including the absurdity of this empire having domain over an Arctic island. Schimanski’s discussion, based in common and contradictory topoi of the Arctic— as a place that is both dark and light, inviting and inhospitable—was a recurring theme throughout the day. John-Alder repeated this thread in her discussion of Ian McHarg, a landscape architect from Glasgow, who contributed both a narrative, personalized and scientific understanding of design through his famous book, Design With Nature. John-Alder pointed out that McHarg’s tension between the idyllic qualities of nature and the gritty urbanism of Glasgow heightened these binaries for the fields of landscape architecture, urban planning, and design. Returning to the Arctic, Arvid Viken, a tourism management professor from University of Tromsø, reiterated the romantic and troubled topoi of Svalbard as a pristine and vulnerable landscape that is neither industrial nor modern. Yet, all of these portrayals are true of the place, he reminds us. Indeed, Viken characterizes the romanticist notion of Svalbard as one that is propagated by the natural sciences and the tourist industry of that archipelago. He asks at the end of his presentation on what moral grounds we can continue to proffer tourism as a main economic import for a remote place like Svalbard. Do humans even belong in a place that has no indigenous human population?

Aileen Espiritu, in her presentation exploring the rhetoric of the Barents region versus the Arctic region, probed the political issues surrounding the naming conventions of these locales in the high north. She points out that the creation of the Barents region was primarily a mission for peace among the four countries of the high north: Russia, Norway, Sweden, and Finland. The Arctic region, however, is much larger, forming an economic basis that extends across the whole of the northern part of the world. Her discussion focused on the political emphasis that the Arctic receives globally, rather then the Barents, and this political emphasis was taken up locally in other speakers presentations.

For instance, Stepa Mitaki showed us the interactive, participatory, online map that he has made, My Murmansk, which allows residents of the town of Murmansk to engage politically with the local government to improve the area. Larissa Riabova and Vladimir Didyk continued the discussion of Russia, by contributing more information about how single-industry towns such as Murmansk are treated within that country’s political and economic systems. Single-industry towns that focus on mining, logging, electrical production, and shipbuilding, which are a majority of the 342 towns in Russia that occupy this status, face serious social problems such as falling populations, housing shortages, and a general under-supply of social infrastructures. The single-industry towns make up 25% of the Russian Arctic population, and yet are not well supported by the government, still functioning as corporate towns run by the industries that inhabit them. A few of the single-industry towns that focus on gas and oil production have begun to ameliorate these social issues, mostly in the cases where the industry itself has required social codes for its employees and has helped to improve the local health and educational infrastructures for its employees and residents. Highlighting these economic and political issues in the high north are important to begin breaking down the binaries in popular thinking that the Arctic is both beautiful and tragic, when really the picture is much more complicated.

Another example of making the unseen more visible in this conference came in Stine Barlindhaug’s presentation on participatory GIS mapping in Finnmark. As part of her dissertation research, Barlindhaug interviewed residents in one area of Finnmark, a part of Norway that remains 80% unmapped on public land use maps. Her goal was to uncover cultural heritage sites that date back 6000 years. She was able to recover 3000 cultural heritage sites, as well as the spaces in between these sites that mark hunting and herding paths – also an important spatial component to cultural heritage that is often lost – when this county had only 1000 cultural heritage sites mapped previously. This participatory cultural heritage recovery project of the Sami people in Finnmark is an important contribution for this indigenous population.

Silje Figenschou Thoresen’s presentation on the Indigenuity Project—an exhibition work, website, and postcard display—marks another important contribution to showcasing Sami culture in the high north. Thoresen’s project includes photographs and stories about the ingenuity of the indigenous Sami population, and included examples of what she called “primitive design,” that is design and design strategies that are accessible. For instance, she showed a photograph of a floating dock that was made from completely recycled materials or a staircase that used pallets as the support structure. These palettes had not been cut down but remained whole because, in this Sami design tradition, these materials will be used only temporarily in this one design, and will be likely torn down and reused in another project in 5 or 10 years. By creating a traveling exhibition and website for these designs, Thoresen is able to showcase that there is a design tradition, primitive and hard scrabble as it may be, within this culture that is often mistakenly only seen as rural and poor.

The final component to the Constructions of North conference included posters completed by the MA students in landscape architecture at the Tromsø Academy of Landscape and Territorial Studies, which is jointly run by University of Tromsø and the Oslo School of Architecture and Design. These posters, presented in the hallway of the building we met in and juxtaposed against the Arctic Frontier conference’s other poster session in the atrium, showed the remarkable design thinking and visualizations that masters students in this new program are performing.