Fields and monuments

After some hours of being on the road and stopping now and then to observe the landscape we turn a corner and suddenly instead of the expanse of rolling hills and rocky outcrops covered in autumn birch is a wide and open valley. The road bisects this unexpected space and we all comment on the enormous fields. In the bright sunlight we see that they are already all mown. This is Zapadanya Litsa River.

Peter reminds us that once near Murmansk there were large dairy farms. The scale of these two stretches of absolutely flat earth remind us of earlier collective farms. Kjerstin tell us how tough it is to grow food this far north. Perhaps a hay field. We drive through the centre of the pale yellow and green earth and traffic streams past us in the opposite direction, feet to the floor now the corners have gone. We slow down and turn into a set of two monuments that commemorate the Russian achievements and losses in pushing back the German advances. Victorious but at a huge cost of life.

These are the plains and surrounding hills of horrific loss and yet they today are bathed in bright sunlight under a cloudless sky. To the right there is a monument that contains the name of each of the 30 000 or so Russians lost here. The black plinth extends horizontally to the left, name after name etched into the stone in small columns. The scale of this loss is silencing.

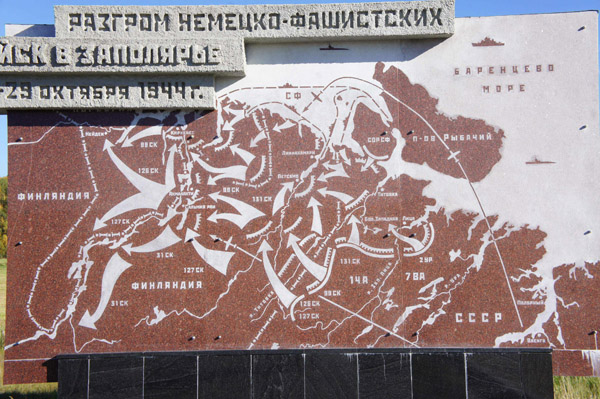

We walk over to a second monument that stands with its back to the field. It is flanked by two maps etched in matt white onto the mottled red granite. They tell of the war moves and their imagery is heroic. On this maps are the outlines of boats and planes and task.

Just behind the maps we see a gigantic harvester. It is stock still on the flat earth, paused perhaps at the turn on long lines of passage. The is no one in in sight and the tractor is relatively new.

We look again at the maps and trace the progress of victory, socialist realist concrete emblems in the space behind us, one appearing to be three concrete bayonets reaching 30 m into the sky. We discuss the scene, the battle scenarios that preceed our short visit.

And when we turn to walk off the paved area onto the field we see that the giant harvester has left us and is now a kilometre down the field, nearly out of sight. We are reluctant to actually walk onto the field. As if on a beach we are lingering on the ‘shore’ of the field, on the sandy strip separating it from the landscaped space of the monument.

Beaches generally perform as a marker of the limit of human space. They leave us painfully singular as human figures, hominids of sorts, left in a material space consisting only of a few elements. This beach performs not as a crude existential reminder, but opens a historical abyss in the horizontal expanse around us. As Andrew runs onto it all the same, in remembrance of his childhood in Zimbabwe. They leave us painfully singular as human figures, hominids of sorts, left in a material space consisting only of a few elements. This beach performs not as a crude existential reminder, but opens a historical abyss in the horizontal expanse around us. Andrew runs onto it all the same, in remembrance of his childhood in Zimbabwe.

Peter picks up a handful of the chaff. In it we see a head of oats, shorn from these battlegrounds. Above us the enamel blue sky. To one side the uniform painted grey of a single large military tank that sits motionless against the hum of traffic on the highway.

Field and monument intertwined. Harvester and tank. A scene of regeneration, the season’s end unreal in this extended summer so far into September. Concrete and soft sandy earth, a site of strategic manouevres, today both bucolic and forever bruised.