Murmansk: a coastal city?

Forged by its strategic location and by geopolitics, Murmansk has been the primary port city in the Russian Arctic since it was established in 1916. With access to ice-free routes to the Barents Sea and open waters to the West, Murmansk has been a strategic military port and indeed has been witness to two World Wars.

Significantly, Mikhail Gorbachev put the city on the world stage when he appealed for making the Arctic a zone of peace in his 1987 Murmansk speech.[1] More recently, the Murmansk port has burgeoned as an economic hub for the transhipment of minerals and raw materials from mines on the Kola Peninsula and oil and gas from the Russian North and West Siberia. The port of Murmansk is indeed highly industrialised and militarized. I interrogate whether there is any room for human scale activities along the coastline of the city, and whether the Murmansk city government can reasonably include such considerations in its long-term strategic planning. By analysing future planning documents, the city administration website, news media, and speeches, I analyse briefly the tension between the port of Murmansk dominated by big business and federal regulations, and the city of Murmansk and its drive to diversify and grow its economy. I argue that the division of political jurisdiction between the port, that appears to be controlled at the federal level, and the Murmansk city administration is markedly separate, hampering not just the possibilities of sustainable economic development within the city, but also citizen’s use of the waterfront so important for their livelihood yet out of bounds for their leisure and recreation.

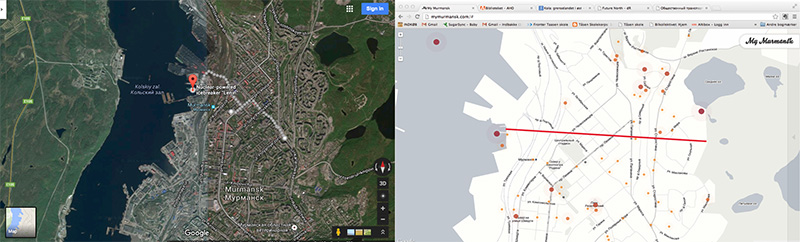

While undertaking a transect that our Future North team walked in September 2013, the inward-looking strategies and industrial economic policies that have built the city of Murmansk since 1916 was evident. Starkly obvious is that city planning is superceded by the transportation needs of the entire minerals-rich Kola region with the waterfront flanked by a tangle of railroads and the shores overwhelmed by hills of charcoal and loading canes. In a sense then, Murmansk is a service city, providing the rest of the region that brings mineral wealth to the entire Murmansk region. Nevertheless, as our transect revealed, the city itself and its citizens very much focus on the livability of its neighbourhoods and city streets illustrated by neighbourhood flower and vegetable gardens made to beautify the city’s cementscape. Though since our transect in 2013, owing to the low oil and gas prices, the sanctions against Russia because of the annexation of the Crimea and the ongoing conflict in Eastern Ukraine, buildings and streets not targeted for renovation because of the 100th anniversary continue to decay. This is particularly acute on the Lenin Boulevard with some of the more historic buildings visibly falling apart.

Maps courtesy of MyCity and Google – DigitalGlobe, CNES/Astrium.

Maps courtesy of MyCity and Google – DigitalGlobe, CNES/Astrium.

Building the “hero city” — Murmansk

By all accounts, the last city created under the Tsarist Empire, Murmansk, was the quintessential Soviet city – industrialised, boasting modernity, a robust population, heroism (awarded in 1985 for its role in the Great Patriotric War), and providing economic revenue for the running of the state and Communist ideology. It was also one of the Soviet state’s centre-pieces for industrial shipping, development, and population growth and presence in the Russian Arctic. It was only second to St Petersburg in terms of volume of transport from their respective ports.

Murmansk as an industrial transport centre in the high Arctic began resulting from the Russian Empire’s involvement in the First World War as the ports on the Baltic Sea were being closed off. Murmansk as a city with a significant industrial port has deep roots both in its fleeting but venerable Tsarist past and its more significant Soviet development. The necessity of building transport infrastructure – a railway, from Petrozavodsk in the South led to a workforce in the tens of thousands, including Russian peasants, Austrian prisoners of war, and Chinese labour.[2] The construction of communication transport infrastructure was the foundation for a permanent population living in Russia’s High North. Inhospitable, remote, bitterly cold, and undeveloped, Murmansk nevertheless thrived because of the investments made by the central Soviet State in mining the Kola Peninsula and thus the need to transport the commodities from the port of Murmansk. In many ways, the goals of Murmansk’s early days are no different from the development aims today. The mineral riches on the Kola have been massively exploited and sold as hard-currency revenue for the state – both Soviet 1917 to 1991 and Russian from 1992 to present day.

Significant, however, is that while the newcomers to Murmansk in the 1910s,20s, 30s, etc., were incited to move to Murmansk from other parts of Russia and the Soviet Union — overwhelmingly from Southern Russia, Ukraine, and the Baltic Sates, offering high wages, promises of apartments, and benefits, those who have stayed express aspirations beyond just their jobs and benefits. With identities firmly rooted in place, they wish to see a city that engages its citizen in local-level development including human-level access to the sea. This explains the ambitions for a renovated and accessible waterfront to be created in celebration of the 100th anniversary of Murmansk City this year, 2016,[3] and into making it into a tourist port for cruise ships. As of the Summer of 2016, however, most of the tourist activity was generated by interest in the icebreaker Lenin, which is docked at the only accessible warfront in Murmansk City. Accompanying the Lenin is an impressive mural telling its history, but in Russian only, which limits understanding of that tourist attraction for many. Around the ship itself and on the quay, there are places for buses to park, but no places for people to sit or spend any time on the docks. However, the city and the oblast’ (provincial) administration have promised a meeting place nearby with the restoration and renovation of an historic building on the waterfront.

Murmansk waterfront, June 2016. Photo: Espiritu

Murmansk waterfront, June 2016. Photo: Espiritu

This is a photograph of the planned public space, with a café, near the Icebreaker Lenin’s quay, taken on 23 June 2016. While the city has been preparing for and indeed celebrating its 100th anniversary, the official Murmansk celebrations are planned for early October 2016.

Analysing discourses

Overwhelmingly, however, and outside the frame of the 100th anniversary celebrations, discursive plans for the Murmansk port have focused on the ports as an enormous industrial resource. Thus, the concentration has been on continued expansion in anticipation of climate change leading to ice-free Arctic waters making possible the transshipment of minerals, oil and gas, and possibly consumer goods from Asia to Europe. Reflected in official documents, speeches, meetings among the municipal and provincial governments, the shipping and industrial stakeholders, as well as the long-term developmental plans have diminished any objectives regarding human-level and tourist access to the waterfront. The current governor, Marina Kovtun, declares that creating an “Integrated development of the Murmansk Transport Hub” as one of 17 ambitious plans that will boost the Russian state’s promotion of an Arctic Zone.[4] Hence, Murmansk will continue have its place as a leading force in the economic prosperity of the country.

Indeed, an urban transect our research team walked in 2013 from a residential district atop Murmansk city down to the Lenin Icebreaker revealed having to cross a rather formidable industrial park and railroad transport area in order to gain access to the water. The crossing was only possible on a ribbon of steel and cement overpass that overlooked the railroad transporting still the most important commodity for the Murmansk port – dirty coal. In stark evidence is the dissonance between the social people-centred history of the 100 years of building of Murmansk depicted in the city’s official website[5] and the big industry priority of both the city and especially the oblast’ governments.

Murmansk is not alone as an industrial city following its well-worn path to anticipated wealth and prosperity. Arctic cities that have historically relied on heavy resource industries and its industrial transshipment are caught in the groove of this dependence on the one big thing that has the potential to fund all of the social, economic, infrastructural, and cultural needs of a place. For some cities in the Arctic, this has meant diamond mining (Mirnyi in East Siberia and North West Territories, Canada), oil and gas (Hammerfest, Norway), mining and processing nickel (Norilsk, West Siberia), coal (Longyearbyen and Barentsburg, Norway), and industrial shipping (Murmansk, Russia). It would take a remarkable shift in mindset for most of these remote, resource-rich regions and cities to change the focus of their mainstays to something more sustainable, human-scale developments. Reliant on non-renewable resources or their transshipment, no other economic enterprise seems as promising. And so we are left with a Murmansk that could develop a human-centred waterfront that has the possibility to grow sustainable tourism, attractive accessible spaces for recreation and habitation, but the city’s political will still gravitates towards what it knows best – serving as an industrial transport hub for the resource-wealth of the Kola Peninsula, and unfortunately leaving out the endless possibilities for human-scale developments that we see in other world cities such as Portland, London, Glasgow, Oslo, Helsinki, etc. – cities that have transformed once industrial cites to living, commercial, and recreational spaces for its residents and visitors alike.

Aileen Aseron Espiritu is a researcher at the University of Tromsø – The Arctic University of Norway.

*Funded from the Arctic Urban Sustainability in Russia project (2012-2015) under the NORRUSS Programme and from the Future North (2013-2016) project under the SAMKUL Programme of the Research Council of Norway. Paper presented at the Arctic-COAST I: Indicators, Resilience, and Governance in Arctic Coastal Social Ecological Systems Murmansk, Russia, on the nuclear icebreaker “Lenin” 23-25 June 2016.

[1] Mikhail Gorbachev, “The Speech In Murmansk At The Ceremonial Meeting On The Occasion Of The Presentation Of The Order Of Lenin And The Gold Star Medal To The City Of Murmansk, 1 October 1987” (Novosti Press Agency: Moscow, 1987), Pp. 23-31. Accessed 18 June 2016 From https://Www.Barentsinfo.Fi/Docs/Gorbachev_Speech.Pdf.

[2] Gennady P. Luzin, Michael Pretes, and Vladimir V. Vasiliev “The Kola Peninsula: Geography, History And Resources,” Arctic Vol 47, No. 1 (March 1994): 1-15.

[3] Atle Staalesen, “Building a tourist sea port in Murmansk,” Barents Observer 09 March 2012. Accessed 01 September 2016. http://barentsobserver.com/en/business/building-tourist-sea-port-murmansk

[4] Murmansk Regional Government, “The project is the integrated development of the Murmansk Transport Hub entered in the list of promising projects in the Russian Arctic,” (“Проект комплексного развития Мурманского транспортного узла вошёл в перечень перспективных проектов, реализуемых в российской Арктике,”) Accessed 5 June 2016 http://gov-murman.ru/info/news/171807/.

[5] ”100 Страниц Истории К 100-Летию Мурманска” (100 pages of history towards 100 years) Accessed 5 June 2016 http://vmnews.ru/proekty/100-stranic/2015/04/16/100-stranic-istorii-k-100-letiu-murmanska.

Great post